About Klaus Petrus

Klaus Petrus is a photojournalist and philosopher. His reportages document life in conflict zones, with stories of people in flight and at the margins of society, and he also examines the hidden realities of large-scale livestock farming.He has received the Swiss Press Photo Award as well as several other prizes for his work.

Current books (selection)

Spuren der Flucht [Traces of Flight]. Aswad, 2025.

Am Rand. Reportagen und Porträts [At the Margins: Reportages and Portraits]. Christoph Merian Verlag, 2023.

You have been working as a journalist for many years, studying people at the margins of society as well as the crises, wars and circumstances that have pushed them into these precarious situations. Before that, you taught philosophy as a professor at the University of Bern. This sounds like a radical life change, was it really such a big change or do these two worlds actually have something in common?

At first, I really could not see any link between teaching philosophy in the academic world and my current work as a journalist. At the university my focus was on theoretical philosophy, especially philosophy of language and logic – these fields are highly abstract and do not have much relation to the real world. Looked at in this way, there was not much in common at all – in fact, there was quite a lot that I needed to forget. The academic style of writing, for instance, does not have much at all to do with journalism. They are, essentially, two different languages, but over the last few years I have realised there is a common thread linking philosophy and journalism.

Which is?

Scepticism is everything in philosophy. Here we have to question everything we assume to be correct or true. We always have to ask whether what we see before us is really the same as it appears, or could everything be different?

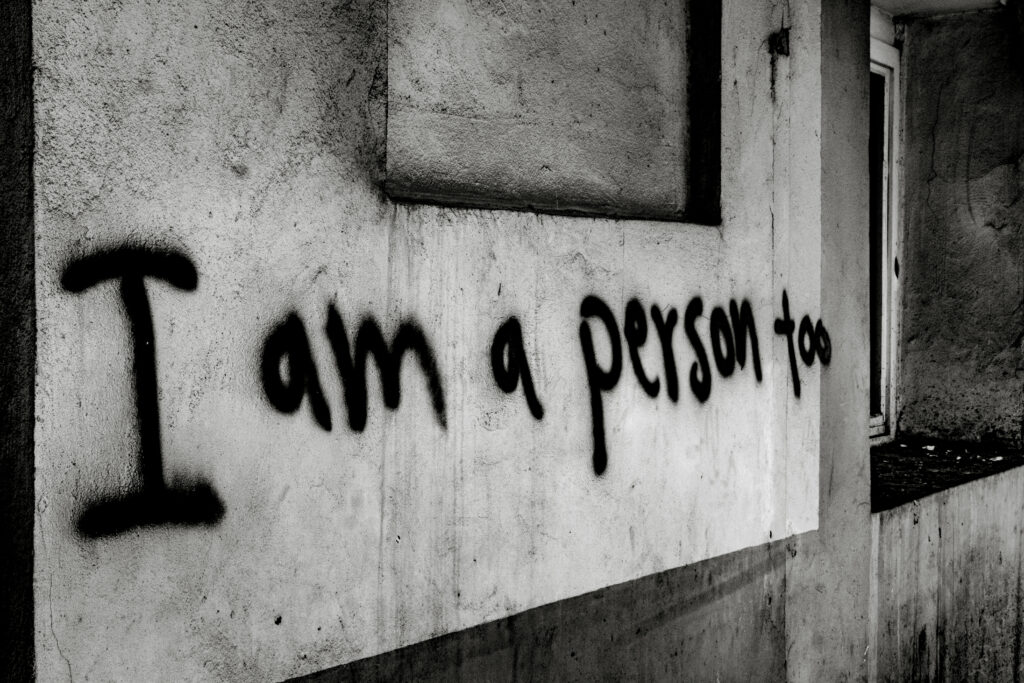

This scepticism also plays a key role in journalism, where we also need to ask if things might be different from the images we have concocted in our minds. This is an issue which really preoccupies me: as journalists, how can we question the preconceived images in our minds – stereotypes, prejudices, even enemy images – and, ideally, put different images in the minds of people?

Shifting preconceived images in the minds of other people does not seem to be an easy task.

It is not. In fact, it is bound to fail. That is my own experience, in any case. But we still have to try. We are, once again, living in an era with a lot of prejudice and enemy images, with people thinking things are either black or white, and that is dangerous. In my view, exposing how such enemy images arise, how effective they are, and what counter-images might look like, is one of the main responsibilities of journalism.

When you refer to “images in the mind,” you mean images in the figurative sense. As well as working with texts, however, you are also a photographer. What, for you, is the role of photographic images, for example in relation to people at the margins of society?

Many of the images in our minds are indeed produced by us photojournalists. This means we have a certain responsibility. By repeatedly taking the same photographs – whether from war zones, for example, or of “the refugees” or “the marginalised” – we do not merely create pictures that are tedious because people have seen them a thousand times. By producing only images that people expect to see, we also run the risk of reproducing stereotypes. That can be dangerous, as I said.

Could you elaborate on this?

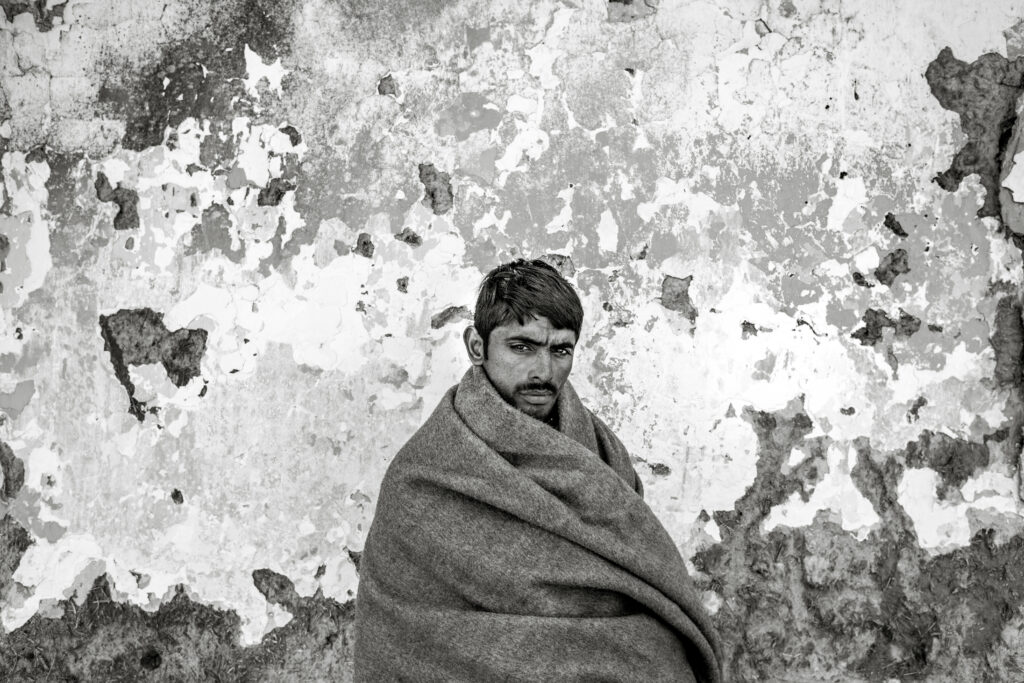

I can try to illustrate it with an example that, somewhat jokingly, I call my “journalistic awakening.” Over an extended period while working on a reportage about refugees in the Balkans, I often went back to the same locations, meeting people who had been stranded there for months and, in some cases, even years. One day, I had a long conversation with a young man from Pakistan and we literally talked about everything under the sun. Eventually, I asked if I could take a few portrait shots. He covered himself with a blanket, stood against a wall and, suddenly, he stopped laughing and joking. As I pressed the shutter, he said: “You see, we have learned to pose for you!” He was not deliberately play-acting and trying to deceive me, but this confirmed my uneasy feeling that mutual expectations are often already set in stone: as journalists, we already have a certain idea of the pose in which we want to portray a refugee. The migrants, for their part, know what we want to see most. Of course, this is somewhat exaggerated. But this is precisely how “typical,” only too familiar images become lodged in our minds. And if this is the only way we then see a refugee, we reduce the person to an image, an image that, quite possibly, has very little to do with who they really are.

In your new book “Traces of Flight”, you attempt to use your photographs to do precisely this: offer a different perspective on migration. How did you approach this project?

It just kind of happened on its own. As I already said, over a period of many years I kept going back to the same border sites in the Balkans that provided shelter for refugees – not just for days or weeks, but, in many cases, for months, even years. As a result, my focus changed over time, shifting away from conventional stories of escape and towards everyday scenes of life in these desolate places. The photographs that emerged depict people waiting, playing, cooking, sleeping, laughing, despairing – the fact that they are refugees can always be seen in the photographs but it is not the main focus. To put it another way: I became more concerned with showing the human being than the refugee.

A certain closeness is needed, at least in photography, in order to show the human being. Do you have to get physically close to people more in photography than when writing?

I always try to get as close as possible to people, whether I am taking photographs or writing. This is driven by my curiosity, but also by my aspiration to show familiar or expected things from another perspective. To do this requires both time and also closeness. I usually meet people several times, we talk at length, I record the conversations. I do not take my camera out until much later. That can be difficult at times, especially when there are moments during a conversation when I start to think that would have been a great picture! The advantage, though, is that once I do begin taking photographs, the people already know me so they do not pay attention to me anymore.

You have published another book called “At the Margins: Stories of People at the Margins of Society – of the Driven, the Defiant, the Excluded, the Invisible.” Yet many of the people you introduce in these stories live right among us. Why, then, do you still speak of the margins of society?

I actually struggled with the book’s title “At the Margins”. You are, of course, right that we are all in the midst of society, but it seems to me that it is those “at the centre” who define those who are “at the margins.” And, in many cases, those at the centre are in that position precisely because others have been pushed to the margins. In other words, such dichotomies are very much connected with social classes and with relations of power and domination. If we continue speaking of the “margins” of society there is the risk, on the one hand, that these power relations are reinforced. On the other hand, it would be strange – even hypocritical – to pretend that excluded and invisible people, the poor and the displaced, do not exist. They most certainly do: there are people who have less than others – less money, less luck, fewer opportunities – or do not conform to what society sees as the norm. That is a hard social fact with socio-political consequences, and it is precisely this that, ultimately, meant I decided to speak of people “at the margins” of society.

Your book also includes portraits of people who are not at the margins in the conventional sense – for instance, a financially and socially secure client of sex workers, or a psychologist with a preference for particular sexual practices. Why do you still place these individuals at the margins?

Because, ultimately, they also live in a kind of parallel world – a world that shields them from guilt and shame. All the people portrayed in my book lead a kind of double life because they do not conform to social expectations.

The idea of invisible parallel worlds outside established norms reminds me of Michel Foucault. In his analyses of why certain population groups are excluded or marginalised in society, he came to the conclusion that the function of exclusion is to reaffirm established norms. Would you agree with that?

It is interesting that you raise this point. Over the course of my work, I have, in fact, increasingly come to the conclusion that, as a society, we need these people at the margins – this is precisely so that we can reassure ourselves that we have succeeded, or at least have not sunk as low as “those others” yet. This is, in all probability, a profoundly human attitude. And something that occurs across class boundaries, even among those already living at the margins of society. For example, I interviewed sex workers who saw themselves as different from other prostitutes as they said they would never perform certain sexual practices for so little money, considering this “beneath their dignity” and saying they did not wish to sink so low. This, I believe, is a mechanism that a society needs for self-assurance. And norms and conventions that must be observed are part of that self-assurance. In this sense, I do indeed see a connection to Foucault.

If you look back over all the years in which you have worked as a reporter, both in Switzerland and around the globe, what has changed at society’s margins during that time?

When I think of my work on migration, at the EU’s external borders, for example, it is difficult for me to see any progress. I mean progress in the sense of greater awareness of the situation of people on the ground, or in terms of whether there are no other ways of dealing with the problems. What I can see is that borders are becoming more heavily guarded, violence against refugees is increasing, and there is a widening gulf between what is debated at the abstract, political level and what people experience every day at the borders. And this gulf carries the very real potential to divide societies.

And in other areas?

There has been some progress with regard to certain forms of poverty. In Switzerland, for example, the “Housing First” model is being tested for homeless people, and additional emergency shelters are being set up specifically for women and young people. This is definitely making a difference for those affected. In the long term, however, I am still sceptical here. Switzerland is one of the wealthiest countries in the world, and out of its 9 million inhabitants, 750,000 live in poverty, including nearly a quarter of a million pensioners and 130,000 children. There is also the growing number of people living just above the minimum subsistence level who, despite working, are struggling to make ends meet. At the same time, there are those who are absolutely swimming in money, whether they earned it or, as is often the case, they inherited it without having to work for it. We hardly ever talk about the fact that one is connected to the other – that some people are wealthy because others are poor. Instead, we act as though social classes no longer exist.

What future do you see for people at the margins of society?

As I said, I am not particularly optimistic. I am worried that the number of people living in precarious circumstances will continue to rise – specifically, that parts of today’s middle class will slide into poverty and be pushed towards the margins of society. I very much doubt this will change the way we view these parts of society, making us live with greater solidarity as a whole. Instead, I expect new forms of class conflict to emerge. I know that sounds outdated, but that’s exactly what I mean. As far as I’m concerned, the idea of a “levelled society” in which social classes no longer exist is a myth. I do not mean to make it sound like we are devoid of empathy or indifferent towards those who are socially disadvantaged. There is this distinction between the system – politics and the economy, for example – which undoubtedly operates according to the logic of capitalist exploitation, and people’s everyday lives. I am still convinced there is a lot of solidarity when individual people meet each other.

In sociology there is the concept of the “friendly stranger”. This is someone we encounter regularly without ever getting to know them. They are part of our everyday lives, we are pleased to see them but we know nothing about each other. An example is the Surprise magazine vendor I see every day on my way to work.

This is an interesting phenomenon – what lies behind it is something like a visible invisibility. By this I mean that these people are indeed present, we encounter them daily, like the Surprise vendor you mentioned, always standing at the same corner with his magazines. However, for most of us he is visible only in a specific social role – as someone living precariously. The same applies to homeless people, drug addicts or sex workers. It is not that they are hidden from us. But they are visible to us only as a group, in the sense of a stereotype: what we see is someone as a drug addict or as homeless. We do not really see the person, however, the individual before us, someone with a name and a life story. We do not know them, they remain a stranger. I think this is a characteristic shared by most people at the margins of our society: as marginalised groups they are visible to everyone, but as people they remain invisible for most of us.

As well as people you also focus on the situation of animals, especially so-called livestock. Why?

Everything connected to social invisibility is a common thread running through my work. This includes large-scale livestock farming. We of course know that there are fattening pigs, for example, but when was the last time we saw one? In the canton of Lucerne alone, there are more pigs being fattened than there are inhabitants. But we do not see them because they are locked away for their entire lives. A second theme that continually recurs in my work is that of power relations and hierarchies, including in our relationship to animals. The distribution of roles is clear in the Judeo-Christian tradition: we are on top, animals below – because we have subjugated them. This gives rise to a series of questions concerning the political and social injustice of how we treat animals. I use large-scale livestock farming as an example to explore these questions.

Many people do not even believe that large-scale livestock farming exists in Switzerland, however.

Exactly, we still imagine animal farming to be the way it is in the Heidi films: pigs, cows and chickens feeding outdoors, happily mooing, oinking and clucking, under the shining sun and snow-capped mountains. There is an entire industry – state-subsidised, incidentally – that tries to use advertising to implant images like this in our minds. But these images have little to do with reality and, for the most part, are fake. When I publish photographs from large-scale livestock farming, my aim is to create a counter-image: instead of a handful of hens scraping around in a lush green meadow, I show high-contrast black-and-white images from inside factory farms – halls in which 18,000 chickens are confined in very tight spaces, fattened for a few weeks, and then slaughtered. This is not to use such visual language for dramatic effect. Instead it is to create an image that counters those glossy posters in advertisements or the packaging of meat, milk or eggs.

And you pursue the same counter-image strategy with people at the margins? Although, in this case, there are generally no idyllic images to be countered.

In each and every case, I want to highlight the invisibility of actual social conditions. And sometimes that does involve idylls. For example, I did a reportage on seasonal harvest workers in the Bernese Seeland. Each year, up to 50,000 people come to Switzerland from abroad to work in farmers’ fields during the season. And yet we hardly ever see them – socially, they do not exist. It would have been obvious to give them a face in my reportage, and indeed that was my initial approach. But the more I looked at the issue, the more often I returned and spoke with the people, the more I realised I wanted to depict their invisibility. With images showing the work of those who themselves remain unseen. Again, the idea was to create a counter-image. On the advertising posters of the major discount supermarkets, we never see seasonal harvest workers, only Swiss farmers. And there, too, the sun is always shining, everything appears tidy, peaceful, cosy. My images, by contrast, are in black and white, many of them are blurred, and people cannot be made out, only signs of their labour can be seen.

Your description reveals a strong interest in ethical questions.

It’s true that, ultimately, almost all of my work revolves around social inequality. And yes, misery, suffering and conflict all have a certain draw for me – this goes hand in hand with the anger I still feel at this injustice. Yet my concern is not so much the moral question as the social and political conditions that lead to poverty, exclusion, migration or war as the themes I focus on in particular. And then there is something else, which may be surprising: it is always about the story behind these themes, too, and it has to be a good story. I am not interested in a story if it does not at least have the potential to challenge entrenched images – even if, from a moral and ethical standpoint, it might be worthwhile to tell.

You are often on the road for your reportages. What have you learned for your own life from your travels?

That many things are not as we believe them to be. That there are a thousand grey areas, and that, when we take a closer look, the black-and-white images we often need in order to navigate this complex world are suddenly put into perspective. But all this takes time, and there is now less and less time in journalism. Everything has to happen quickly and, as a result, the ability to differentiate suffers, as well as careful observation. But we still have to try. There is another thing on my mind and, although this may sound clichéd, it is remarkable what people can endure in crises. I have seen many situations where it seemed impossible for it to get any worse for those affected – but then it did, it became worse and worse. But they somehow survived. This is impressive and also depressing because it makes crises, wars and catastrophes seem almost normal, something people can get used to, and, basically, that is a horrible idea.

When speaking about people at the margins, we usually also think of integration or inclusion. What role, in your opinion, does education play here?

There is no doubt that there is a very close link between education and social status, this has been proven by countless studies. It is also undeniable that because of their ethnic background alone, for example, people have fewer opportunities to use their education to establish themselves or even simply to integrate. There have been efforts to overcome all this by giving equal opportunities, meaning fair access to education, to everyone. But, as we know, in reality the situation remains different. And this is not only due to the education system. The simple fact that some children or young people acquire forms of behaviour, knowledge or taste “for free” through their family or social environment gives them a tremendous advantage over others from milieus where these resources are not available. The French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu referred to this as “cultural capital,” which is very unequally distributed even in supposedly egalitarian societies and, as a consequence, is a source of social injustice.

Do you think educational institutions have the potential to reduce marginalisation and exclusion?

To continue with the topic that always bothers me in my work, I would say that educational organisations also have to help dismantle stereotypes about people at the margins of our society. One way of doing this, for example, is by calling into question strategies of shaming people and creating counter-images that bring about destigmatisation. In practical terms, this could be taught by incorporating it into teaching materials. Or by using resources created by people from marginalised groups themselves – for example, a book authored by Romany people about their own history, culture and language. Another approach is by establishing direct contact with excluded people, this could be in the form of presentations, workshops or city tours, for instance, where marginalised individuals show the city from their perspective. These are approaches which, today, would probably be described as “participatory.”

One final question – something which you are probably not interested in at all, but if you were to return to the academic world, which philosophy would you teach today?

That is indeed a highly hypothetical question because I really cannot imagine returning to that world. Not because I disliked it – in fact, there were wonderful conditions and a highly inspiring environment for me to work in. It is more because, generally, I try to look forward, not back. In addition, with a few exceptions – such as Ludwig Wittgenstein, who had a great influence on my views on philosophy of language and logic – I hardly read philosophers anymore. Surprisingly, I am now interested in authors I did not pay much attention to back then, especially those from the social sciences. This includes Bourdieu that I mentioned before, he is someone I only discovered in recent years but who, since then, has had a huge influence on me, including as a journalist. So if you ask me, I would maybe combine Wittgenstein with Bourdieu today. I would definitely be curious to see what would emerge from that.

©Klaus Petrus. The photographs are from photo reportages on people in flight and on the topic of poverty.