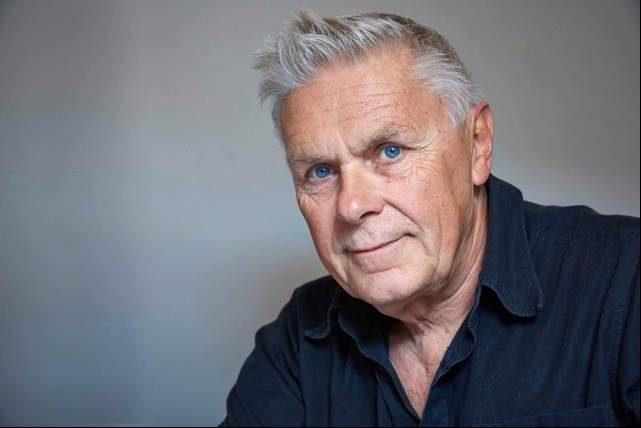

About Eduard Kaeser

Eduard Kaeser was born in Bern in 1948. He studied theoretical physics, followed by the history of science and philosophy, at the University of Bern. Until 2012, he taught physics and mathematics at secondary level. He has published work on issues at the cross-section of science and philosophy. Alongside books, he has published essays and articles in the newspapers «Wochenzeitung», «Die Zeit» and «Neue Zürcher Zeitung».

Artificial intelligence is already part of our day-to-day lives now, yet we talk as if it is still a long way off. Why is that?

Dominant technologies always need to offer something to look forward to. And if they are to become established on the market, they need to be «pimped up» using corresponding promotional tools. This faith in technology can even take on a religious character, especially in the USA, with this technological future seen as the solution to all our problems and concerns.

How intelligent is AI really, today?

In the early days of AI, computer specialists argued about whether machines which were capable of taking on and handling intelligent tasks were themselves also intelligent. The point, or maybe the crux here is, of course, the term «intelligence». It can always be defined such that machines are classed as intelligent.

In particular, AI researchers addressed the question of whether something designed by humans could not only be a match for human skills but could also, under certain circumstances, exceed what is humanly possible. This is an old, deeply philosophical question for which almost all AI pioneers demonstrated a particular flair. That once philosophical climate is now being replaced by one based on economics. The vast majority of young software designers barely consider whether their creations are intelligent or not. All that really matters is whether they can quickly be flogged off on the unrestricted market of smart devices.

But AI is now capable of learning, right?

That learning process is limited and specific. Deep learning is essentially statistics. Today, statistical methods are highly developed, but they cannot be expected to result in a level of intelligence similar to that of humans. Such intelligence demands systematic intervention and imagination. It remains to be seen whether machines can be taught this.

AI learns on the basis of data collection and comparison. A computer requires 10,000 images of birds to eventually recognise a bird straight away; something a child can manage much faster. What does that tell us about different forms of intelligence?

Primarily, that, in essence, intelligence is related to very specific learning situations. Living beings’ intelligence is the product of a long history of evolutionary tests and challenges; challenges which are incredibly varied. There is no question that their intelligence requires data collection and comparison, but that is probably just one small part of the activities which an organism relies upon to cope with its environment. A lot remains to be learned from biology in that respect.

Yet we assume that our intelligence is the model for AI. Is that even correct?

That is a question of the paradigm, the underlying research question. As a leading AI researcher, Stuart Russell, bluntly puts it, «As yet, we have very little understanding as to why deep learning works as well as it does. Possibly the best explanation is that deep networks are deep: because they have many layers, each layer can learn a fairly simple transformation from its inputs to its outputs, while many such simple transformations add up to the complex transformation required to go from a photograph to a category label.» This explanation is not exactly mind-blowing. It is reminiscent of Molière’s satire of opium helping people sleep because of its «dormitive virtue»: a tautology.

«Today, we have a pretty good understanding of computers, yet we are a long way from knowing how the brain works, and even if we were to achieve that level of knowledge, that would not mean that the brain is a computer.»

Do we even know enough about the way we learn and our intelligence to create AI which is on a par with us?

You have hit the nail on the head with that question. Since Alan Turing, AI research has been mesmerised by the idea of delegating everything humans have to do to computing processes. Deep learning researchers like to point out that the layer model of neural networks is a primitive simulation of the activities in the layers of the brain. Today, we have a pretty good understanding of computers, yet we are a long way from knowing how the brain works, and even if we were to achieve that level of knowledge, that would not mean that the brain is a computer. Seen in a sober light, the computer is a heuristic metaphor. And, if we confuse the metaphor with the thing it represents, then we are falling prey to an epochal misinterpretation.

Is it possible that a Turing test could prove successful? After all, it has been passed when humans and machines cannot be distinguished from each other.

To date, Turing tests have been conducted in a very specific, limited setting, in which AI can absolutely excel. The really important question, however, is whether AI systems can also survive in «normal» daily environments, i.e. in settings with ambiguities, fuzzy conditions and unexpected eventualities. In this context, AI researchers refer to the «frame problem». Our actions always take place in a framework of implied, unconscious assumptions which we can refer back to in fuzzy situations. This flexible frame, which never becomes entrenched, forms what we call practical intelligence or common sense. How can this be implemented in AI systems? How can they have common sense? That is the decisive test. And, by the way, Turing was wrong about learning. He wrote, «Presumably the child-brain is something like a note-book as one buys it from the stationers. Rather little mechanism, and lots of blank sheets.» Nothing could be further from the truth.

Or is it not more likely that AI will develop into a completely independent form of intelligence which we will ultimately be incapable of understanding?

It’s true that we are already in a development phase which I refer to as the age of the inscrutable machine. Neural networks are made up of what are often millions of elements which convert a numerical input into a numerical output. This means the machine may develop rules which only it understands. The designer has limited insight, if any, into the inner workings. With each increasing layer depth, the AI system becomes more independent: a black box. This often works surprisingly well and provides staggeringly accurate predictions, the price for this being that it is unclear how this result was obtained. We see an inverse relationship between predictive accuracy and penetrability: The more capable the system is of providing exact predictions, the harder it is to interpret. As such, we are faced with the choice between transparent yet inefficient systems, or inscrutable yet efficient oracles.

«In any case, anyone who sees the triumphal march of smart devices and concludes that an independent super-intelligence will develop in the foreseeable future is rather like a monkey standing on a tree, screeching that it has taken the first step to the moon.»

Let’s go back to the start: AI is already a part of our lives. It has changed how we live and behave. What is going to happen next?

Nobody knows that with any certainty. Yet, we should listen to the hard-headed AI experts. According to Michael Negnevitsky, the author of an authoritative textbook on AI, in terms of learning machines we are currently at the stage of paper planes, compared to supersonic jets. In any case, anyone who sees the triumphal march of smart devices and concludes that an independent super-intelligence will develop in the foreseeable future is rather like a monkey standing on a tree, screeching that it has taken the first step to the moon.

«Metaphors have crept into our everyday language, creating the impression that computers have literally become intelligent.»

And will it continue so subtly that we fail to realise what is happening?

Digital technologies are essentially the technologies of everyday behaviour. Behavioural economics has become a very popular discipline. It has even been awarded a Nobel Prize (Daniel Kahneman, Amos Tversky).

The focus here is on a sociocultural problem: how we are becoming enmeshed with machines. We still have no answer to the question of whether machines can think, but we are gradually getting used to the language of computer scientists and software designers, who frequently talk about computers’ functions as if such devices can think. Metaphors have crept into our everyday language, creating the impression that computers have literally become intelligent. Popular literature is full of such ill-considered metaphors. There are constant references to how computers are taking on an increasing number of human tasks and, inversely, the human body is considered to be a «biological machine» or, recently, a «biological algorithm». This means the machine is starting to creep its way into the ranks of our engineered life forms, as a kind of «subject». We don’t just need it, we live with it, as we live with any fellow human being or animal. We are living in a homo sapiens/robot symbiosis. And there is a real risk here that rather than anthropomorphising robots, we will start to robomorphise humans.

Should we be concerned?

We should be far less concerned about AI systems and more worried about ourselves. After all, we are able to adapt more easily to new technologies than vice versa. We are already hybrids; a mixture of human and device. Just consider the daily practices of how we communicate. Within just a short space of time, this hand-held device which most people carry about with them has become embedded in our psyche. It determines our social manners, our relationship with ourselves and our self-image.

Incidentally, although science fiction is fascinated by extraterrestrial beings whose intelligence is far beyond our own, in fact the aliens are already in our midst, in the form of highly developed automatic systems. The vast majority of the global financial market is controlled by such «aliens» and we have barely any insight into the unfathomable decisions they make. There are chess programs with strategies which even the grand masters struggle to see through, if at all. They come across as intelligent beings lurching about, making each move with a seeming lack of logic and in a random manner, yet regularly checkmating their opponent. As foreign and impenetrable as an extragalactic being.

What do we common or garden users need to learn, to handle AI properly?

The answer to that is simple: we need to learn who we are. But that is only simple at first glance. An advanced understanding of machines forces us to look closely at our self-image: What can machines do too; what is the difference between the human and mechanical execution of skills?

In my view, that is the central question at the start of the 21st century, Alan Turing’s legacy. And that question will not be answered primarily by computer scientists, but by anthropologists, i.e. ultimately by every single one of us. Or at least let’s hope that’s the case.

Do you think that this educational task is being recognised, and action taken?

There are certainly signs that that issue has been recognised in schools, for example in secondary education. I have seen computer science and philosophy teachers working together. What is important in this context is having universities of applied sciences which do not focus only on teaching technological expertise. Universities of applied sciences have shown a high level of interest.

«Teachers and trainers will have to redefine their function in the world of digital intelligence.»

How, on the other hand, will AI change how we learn? Will we soon be taught by holograms?

No. Teachers and trainers will have to redefine their function in the world of digital intelligence. That is also part of the educational task. As I said, what do we humans actually know about our own skills?

How, ultimately, will AI change us?

I can’t answer that question. There are two paths. Some fifty years ago, one of the brightest and most influential critics of AI, the American philosopher Hubert Dreyfus, warned that the risk would not come from super-intelligent machines but rather from sub-intelligent humans. That warning is more relevant than ever.